Philippine Cinnamon: The underrecognized native spice

Many Filipinos, especially those who live in cities, consider cinnamon as an exotic spice. This is perhaps because their exposure to cinnamon is often limited to American pastries, Middle-eastern cuisine, Chinese dishes, etc. Moreover, almost all of the cinnamon in the market are imported. But little do we know that we have our very own Philippine cinnamon, and we have around 19 endemic species of it found across the archipelago.

Philippine cinnamon has been produced and traded since the 1500s. It is locally known or called Kalingag or Kaningag. The name varies depending on the region. Despite its diversity and long history in our country, Philippine cinnamon remains underrecognized.

A bit of history of Philippine Cinnamon

The world knew about its existence through Antonio Pigafetta. The Italian chronicler joined the expedition to the Spice Islands led by explorer Ferdinand Magellan. Pigafetta published his encounter with Philippine cinnamon in the 1500s.

During their expedition, they found a cinnamon tree in Mindanao which the natives call caiu mana; caui means “wood” and mana means “sweet”. Pigafetta described the cinnamon species as a small tree, three to four cubits high, and of the thickness of a man’s finger. The chronicler added that the barks are harvested by natives twice a year. They managed to barter two large knives for 17 pounds of cinnamon.

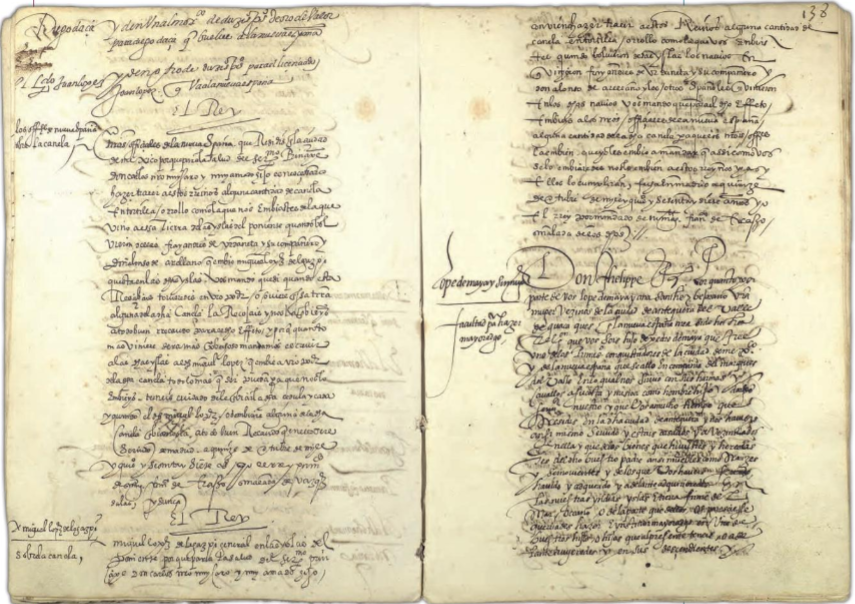

Later expeditions saw cinnamon not only in Mindanao but also in some parts of the Visayas. In 1567, Miguel López de Legazpi shipped 70 quintals (1 quintal is equal to 100 kilograms) of cinnamon for the King Philip II of Spain. The following year, he shipped a consignment of 150 quintals. They had to cut down thousands of Philippine cinnamon trees. Legazpi once wrote to the King that cinnamon was the only article in the land from which they can derive profit.

READ: Food security vs food self-sufficiency

During the Spanish colonization, Philippine cinnamon was traded to the West via galleon trade.

Under the radar

Globally, there are around 250 cinnamon species. 25 species are reported in the Philippines, 19 of which are endemic or can be only found in our country. Out of the 19 endemic species, three are considered commercially viable. These include Cinnamomum mercadoi, which is minty in taste and smell. Cinnamomum mindanaense is closely allied to Ceylon cinnamon in terms of flavor and aroma. Finally, Cinnamomum cebuense, which has a smooth outer bark similar to C. mercadoi.

Philippine cinnamon is mainly used in folk medicine. Locals use the decoction of the bark for loss of appetite, bloating, vomiting, headaches, dysentery, rheumatism, and other ailments. Additionally, our cinnamon has also great culinary use. It can be used to remove the gamy taste in meat, as a flavoring for sugarcane wine, or even as stuffing for lechon! And for creative cooks, as an ingredient to pastries and confectionaries or savory dishes such as adobo and humba.

Although our local cinnamon has potential economic value, it doesn’t have widespread use due to its scarcity. Utilization of it is mostly found in rural areas. Many of our cinnamon species are threatened due to the loss of Philippine forests.

Hope for the species

In 2017, Plantsville Health, a social enterprise company, started working with farmers in Negros Occidental to save the Philippine cinnamon. It all started when November Canieso-Yeo, the founder of Planstville, discovered that the Philippines is home to the coveted spice. This was when she was blogging about organic home gardening and superfoods in 2016.

After the Philippine cinnamon piqued her interest, November started talking with the Negros Occidental Provincial Management Office (PEMO), who pointed to her where Philippine cinnamon grows. This led her to the town of Don Salvador Benedicto, which at that time had only around 50 remaining cinnamon trees. The farmers, not knowing its value, cut down cinnamon trees for charcoal.

November was able to educate the farmers on the importance of Philippine cinnamon, and together, they were able to get funding from the local government. With the funding from the LGU, the farmers were able to plant 14,133 Philippine cinnamon seedlings. It is one of the largest conservation efforts for Philippine cinnamon in the Philippines.

Planstville has already developed several products from Philippine cinnamon, mainly from Cinnamomum mercadoi. They were able to process cinnamon coco sugar, a low-glycemic sweetener, and cinnamon bark chips, which is good for making tea. Plantsville was also able to utilize the cinnamon leaves after getting a big distiller through funding from the Australian Embassy. Their product line now extends to sanitizers and essential oils.

While the market is still dominated by imported cinnamon, the future of Philippine cinnamon as an economically-important tree is getting brighter. Public and private sector engagement in conservation efforts is increasing. And this doesn’t just go for Philippine cinnamon, but to other native trees. This is wonderful news. The increased interest of Filipinos to plant and cultivate native plants gives hope to hundreds of underrecognized and underutilized plant species.