Padala system at the center of terror funding (Story 4/4)

NOTE: The national security researchers of this investigative series are both natives of Mindanao; and have long-term exposure to the local conditions of numerous conflict areas in Southern Philippines.

TO better understand the financial systems behind the Daesh-Maute terrorist organization, one must understand a few basic facts about any kind of modern warfare: First, vacuous articles and misleading propaganda videos get circulated on both mainstream and social media to protect the vested interests of spiritually bankrupt leaders on both ends of the war spectrum.

Second, the spoils of war get divided not only among vicious terrorists but also among a few misguided or coopted politicians, military and police officers.

Third, greed knows no limits, and it grows little by little, continuously. In war time, greed tends to grow exponentially. In a few tragic cases during the Marawi siege, incorruptible team leaders or members of the military were allegedly shot to death by their own teammates over looted cash and gold.

Last but not the least, while there are tons of nitty-gritty details and heart-wrenching stories related to the Marawi siege, one must remember that the ultimate goal of foreign powers which financially support ISIS Central in funding ISIS Philippines is not merely to expand Daesh territory, but to portray the Philippines under the Duterte administration as a weak state. With all the geopolitics at play, reporting from the field is seldom black and white.

Marawi is not Mosul, but it could have been, if not for the incredibly brave and successful counter-attack of the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP). One hundred sixty six of the Philippines’s finest soldiers and policemen lost their lives in this five-month war.

Col. Romeo Brawner Jr., the deputy commander of Joint Task Group Ranao, confirmed with The Manila Times that the Daesh-Maute terrorists seized only less than 20 percent of the total land area of Marawi City from May 23 to December 12 last year to establish an IS enclave in Southeast Asia. During the period, 974 terrorists, 166 soldiers and policemen, and 47 civilians were killed in the war for control over the city.

The financing of terrorism involves several activities including the storing of finances, masking funding sources and even developing infrastructures to manage and transfer funds to terrorist organizations. A proper analysis of Daesh Philippines’ terror funding requires a deeper understanding as well of the traditional Maranao and Muslim culture as well as business practices in Lanao del Sur.

There are three ISIS Central and Daesh-Maute financial systems: money laundering through universal banks, Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas (BSP)-registered private remittance centers, and the informal hawala/padala system in Cagayan de Oro City and in Region 10 or Northern Mindanao

Money laundering and universal banks

Money launderings consists of three phases. The first phase consists of introducing the funds gained from criminal activities into the banking and financial system; this phase has become more and more fraught with risk due to the heightened attention now given to these movements of cash by law enforcement authorities and the standardized requirement for banks to report suspicious transactions.

The second phase consists of putting the funds that have entered the financial system through a series of financial operations, the purpose of which is to mislead potential investigators and to give these funds the appearance of having legal origins. This is the money-laundering phase that often uses offshore mechanisms.

Finally, once these funds are made to appear to have legitimate origins, the funds are reintroduced into the legal economy, through the consumption of luxury items; investments in commonplace assets, including shares in companies, real estate, etc.; and investments in establishments that are susceptible to becoming money laundering machines like casinos, hotels, restaurants, and cinemas where payments are made in cash and where dirty money can easily be mingled.

Terrorist organizations use universal banks to remit money. The ISIS Central made use of specific bank accounts in favor of Isnilon Hapilon to fund at least $1.5 million for the Marawi siege, raising the need to follow the ATM receipts of the terrorists in order to facilitate their prosecution.

One of the biggest challenges that have hampered detection is the confidentiality principle followed by the banking sector. The principle of confidentiality has been used to hide criminal activities including money laundering by some banks.

In the stage of layering in the process of money laundering, money obtained illegally is broken down into smaller amounts then transferred to either a single account or several accounts elsewhere.

Private remittance centers

Remittances can fund acts of terrorism.

Researchers from START’s Global Terrorism Database found that for every remittance transfer between $250,000 and $1 million during 1974-2006 for the typical Sub-Saharan country, one terrorism incident is financed for approximately every one million dollars in remittances.

For 2010, the top 12 recipient countries for remittances, in descending order, are: India, China, Mexico, the Philippines, Nigeria, France, Egypt, Germany, Bangladesh, Spain, Belgium, and Pakistan. Majority of these countries have experienced a lot of terrorist activities. For example, officials from the Financial Transaction Reports and Analysis Center revealed in an international counter-terrorism meeting in Bali that over $763,000 was transferred from foreign countries to fund terrorism in Indonesia between 2014 and 2015.

Given only small sums are required to stage a deadly attack, even modest amounts of funding from foreign terrorist groups pose a significant risk to the region’s security.

In Marawi City, the major private remittance centers are found in Bangolo, Mindanao State University Campus and the Marawi City Hall. In Marawi City, Western Union, M. Lhuillier, Cebuana Padala, Palawan Express, Moneygram, LBC and Transfast are the major players in the remittance business.

According to the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas, the volume and value of remittances are high for the period January to October 2017 compared with the figures of the previous year. Specifically, in Region 10, one branch of the largest BSP-registered private remittance center recorded a 200-percent increase in internal remittances from P15,000 per day in February 2017 to P43,000 per day in October 2017. The remittance center processes foreign remittances at a steady bulk of 25 percent and internal remittances at 75 percent. The remittance centers also processes requests from non-local residents who transact with their office.

One branch of the second largest BSP-registered private remittance center registered a 200 percent increase in internal remittances from P10,000 per day in February 2017 to P38,000 per day in October 2017. Last year’s remittance figures went up from P10,000 in January 2016 to P25,000 per day by October 2016. The remittance center processes foreign remittances at a steady bulk of 30 percent and internal remittances at 70 percent. The remittance center also processes requests from non-local residents who transact with their office.

The largest BSP registered pawnshop in Region 10 reflected a daily transaction of P10,000 in 2016 compared to P40,000 in 2017, representing a 200 percent increase. Internal remittances accounted for 60 percent while foreign remittances accounted for 40 percent from 2015 to 2016. Then in 2017, internal remittances accounted for 80 percent of the total transaction compared to 20 percent for foreign remittances.

According to a local Labor department official, there were no marked increases in OFWs deployed in the period January to October 2017. Moreover, there was only one large enterprise that opened in the area during the period. The absence of new work possibilities for the locals does not explain the large increase in internal remittances.

In the absence of any plausible explanation, the evidence points to the possible terrorist financing carried out by the ISIS Central to its newly recruited local fighters, who may be sending the cash remittances to their respective families.

In addition, this marked increase in internal remittances may also be explained by narco-politics dominating the areas of Lanao del Sur and Lanao del Norte. The drug trade may be fueling increasing remittances. These possible explanations can only be fully determined through an increased regulatory power and framework by central bank officials in this region. There is a need to study internal remittances in the same manner that the government closely studies OFW remittances.

Hawala/padala system

Informal value transfer transactions are based on trust and rarely leave any traces. Informal value transfer methods are defined by counterterrorism author Nikos Passas as: “…any system or network of people facilitating, on a full time or part time basis, the transfer of value domestically or internationally outside the conventional, regulated financial institutional systems.”

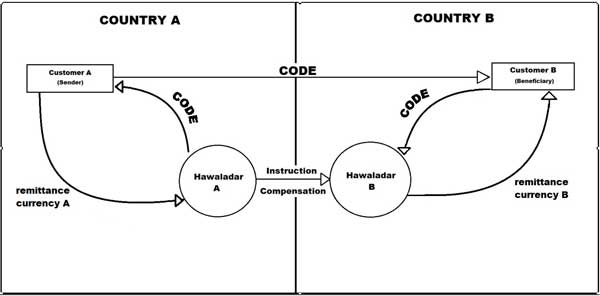

Money is transferred between two parties living in two different countries but cash does not cross borders. The money never enters the conventional banking system. The transaction is based upon a single communication between the two “hawaladars” and is usually not recorded or guaranteed by written contract between them. (seediagram).

Passas notes that terrorist organizations such as Kashmiri, Hamas, Jemaah Islamiyah, and al Qaeda have been known to use hawala transfers. According to Matthew Levitt, director of the Stein Program on Counterterrorism and Intelligence of The Washington Institute for Near East Policy, the hawala is a perfectly legitimate form of financing.

In the local setting, there are hawala/padala informal remittance centers around the 15 barangay (viilages) of Cagayan de Oro. Most of the relatives of the OFW workers based in Qatar, Kuwait United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia resort to this system of remittances. Previous ADB estimates state that the amount coursed through informal systems and “padala” practices could amount to a minimum of $1.5 billion per year.

The qualities of simplicity and anonymity of the operations of the hawala/padala system have also attracted individuals and groups engaged in criminal activities such as money laundering, gambling, smuggling or the financing of terrorism. Clients use that system because of its quick and cheap international remittance service. Criminal elements also engage its services to hide the origin or destination or break the audit trail of money.

Economic and cultural factors underpin the attractiveness of the hawala system. It is less expensive, swifter, more reliable, more convenient, and less bureaucratic than the formal financial sector. Hawaladars charge fees to generate income. The fees charged by hawaladars on the transfer of funds are lower than those charged by banks and other remitting companies, due to minimal overhead expenses and the absence of regulatory costs to the hawaladars. To encourage foreign exchange transfers through their system, hawaladars exempt expatriates from paying fees. In contrast, they reportedly charge higher fees to those who use the system to avoid exchange, capital, or administrative controls. These higher fees often cover all the expenses of the hawaladars.

The system is swifter than formal financial transfer systems partly because of the lack of bureaucracy and the simplicity of its operating mechanism; instructions are given to correspondents by phone, facsimile, or e-mail; and funds are often delivered door to door within 24 hours by a correspondent who has quick access to villages even in remote areas. The minimal documentation and accounting requirements, the simple management, and the lack of bureaucratic procedures help reduce the time needed for transfer operations.

Law enforcement officials need to identify funds early on in order to nip terrorist activities in the bud. These efforts include—but are not limited to—taking action on money laundering activities, remittance services, and the hawala system. While we are fully aware that terror funding cannot be solved easily, it should awaken as much determination and creativity as possible. The main goal is to make all financial transfers by Daesh-Maute as difficult as possible.

via Manila Times

THE MANILA TIMES INVESTIGATIVE REPORT: “MONEY TRAIL OF THE MARAWI SIEGE”

Drei Toledo (drei.toledo@manilatimes.net), Mimi Fabe (mimi.fabe@manilatimes.net)